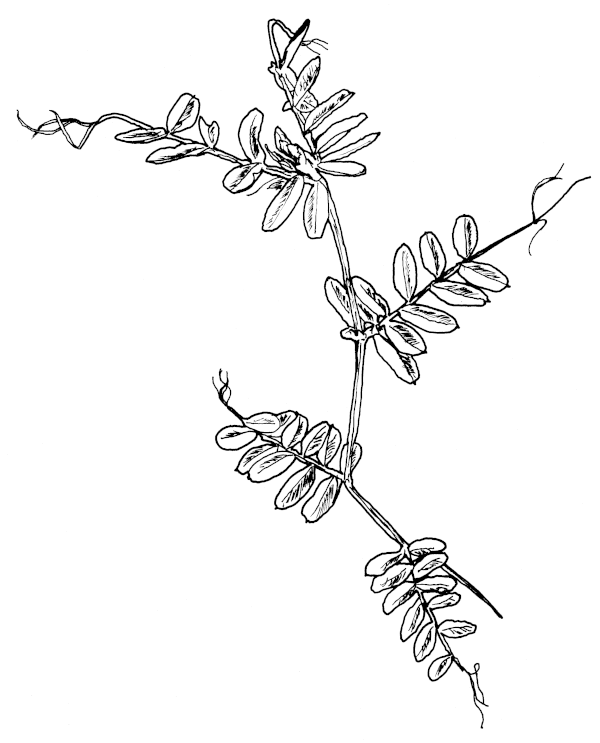

Figure 9.1: Poison Ivy.

| Chapter 8 | Introduction | Chapter 10 |

The little poem above is useful for identifying different grass-like plants, many of which are used in making rope. Sedge stalks have triangular cross-sections. They have edges. Rush stalks are round and smooth all the way up. Grasses have joints, or knees, along the stalk, like the joints in a bamboo cane.

But not all rope fibers come from sedges, rushes, or grasses. Many cordage fibers also come from vines, shrubs and even trees. Seeds, roots, leaves, and bark are all used to make rope. Before Hemp and Flax were introduced to Europe, the inner bark of trees, or bast fibers, were often used for rope.[030] [290] [380] [390] [430] [613] [630] [905]

However, it was entirely in Latin, and did not have illustrations. John Hill, M.D., a contemporary of Linnaeus, in his 1770 "The Useful Family Herbal", did not agree with the new method of naming plants. In Hill's book:

"The Plants are aranged according to the English Alphabet, that the English Reader may know where to find them : They are called by one Name only in English, and one in Latin ; and these are their most familiar Names in those Languages ; no Matter what Caspar, or John Bauhine, or Linnaeus call them, they are here set down by those Names by which every one speaks of them in English."[415]

The ropemaker of the 1770s would not know the modern Latin Names, but they are included here to assist the modern reader.

The colonial ropemaker would be unfamiliar with the natural fiber ropes commonly available today. Jute, Manila, and Sisal were not imported into North America until after 1800. If a plant isn't native, note is made of its probable introduction date.

Read up on your local poisonous plants. It's better to get familiar with these plants by reading than personal experience. (This is the voice of personal experience.) If you find a vine with lots of tempting hairy rootlets sprouting out of the side, it's probably Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Leave it alone.

Figure 9.1: Poison Ivy.

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) is another nice vine, and the younger shoots can make good, strong cordage. But some people, myself included, react to it like Poison Ivy.

There are many useful plants not listed here. "It has been estimated that over a thousand species of plants are yielding fibers in America alone..."[730] If you find a plant in your garden, or on a walk, and it looks like it might make good rope, try it.

Richard Graves,[295] has a simple three step test for plants:

Remember, different parts of the same plant have different properties. If the leaves don't hold, maybe the bark or the roots will work. How much time and effort you spend looking for good fiber will depend somewhat on how badly you need that piece of rope. It's better to become familiar with the plants, and the parts of plants, that can make rope when you have the time, and not scramble if you need to make rope on short notice some day.

These are my experiences. Your results may vary. Things like soil, weather, season, sex, many things can affect the fibers in plants.

So here are the plants I've used, with a nod to John Hill, "... aranged according to the English Alphabet...", using the names I first heard them called.

|

Basswood

[030]

[254]

[265]

[380]

[670]

[905]

[1045]

The Basswood tree is in the same genus as the Lime and Linden trees of Europe. References to "lime bast rope" are talking about rope made from Tilia bark. This was an important fiber source for the Native Americans and the Vikings. The native range for Basswood is from Virginia to the Dakotas, Canada to Florida. Basswood has dark green, saw tooth edged, heart shaped leaves. Light green, smooth edged, long oval bracts at the flower/seed stems makes the basswood easy to identify, even at a distance. The traditional method for processing large amounts of basswood bark is to cut long, straight trunks, with few side branches. In Europe, these might be coppiced trees. The bark is stripped from the trunks and retted for several weeks. Then the inner bark is separated from the outer bark in long ribbons which are rinsed and dried. For smaller jobs, wind felled branches often have pre-retted bark, and you can make cordage without the wait. It is possible to split the basswood bark down to very fine fibers and make a fine thread, but for most ropemaking, the ribbons are twisted just as they are.

|

Figure 9.2: Basswood - Leaves, Bracts, and Seeds.

|

|

Bermuda Grass

Root[380]

[285]

The roots of Bermuda Grass that make it so hard to pull out of your garden also make a strong, though coarse, rope. Bermuda Grass was most likely introduced to the Colonies in the early or mid-1700s. It was well established by 1803.

You want the fine, wiry roots, not the thick, white rhizomes. Just pull the roots off

of the plant. You might even have to cut them off, they are very tough. Rinse the sand

and dirt off, let them dry for a day or two, and you are ready to go.

|

Figure 9.3: Bermuda Grass Roots. |

|

Blackberry

family[380]

[285]

You can strip the leaves and thorns off long vines with a good pair of heavy leather gloves. Lacking gloves, you can carefully grab the end of a vine, between the thorns, and rub a stick down the vine, knocking off thorns and leaves before you cut the vine. The outer bark peels off easily in the late Spring, early Summer, but later in the season, you may have to pound on it a bit to loosen the fibers. The outer bark and fibers have a waxy feel, and the fibers are stiff and coarse. Might benefit from retting and hatchelling.

The berries are tasty.

|

Figure 9.4: Bramble. |

|

Burdock [254]

The Greater Burdock is known by many names. These include: Edible Burdock, Lappa, Gobo, Beggar's Buttons, and even Happy Major, though I don't know why. The Greater Burdock can grow to five feet tall, and the burrs will get caught in your hair, your dog's hair, and get stuck in your socks. The fibers in the stalks of the plant are coarse, stiff, and strong. This makes for a stiff, coarse rope, good for hauling and lashing, not for fishing line. You can separate the fibers by beating the stalk with a stick on a stone, or splitting the stalk and scraping with a dull knife. I've found this easier to do when the stalks are still green and fresh.

Originally from Asia, the Greater Burdock is listed as an invasive,

noxious weed in many states.

|

Figure 9.5: Burdock. |

|

Cattail[742]

[500]

[635]

[712]

The Cattail, or Bulrush, is a very useful plant for food and for fiber. The distinctive "hotdog on a stick" shape is usually found in standing water, or damp ditches. The long leaves are shredded, retted, and twisted. There are some references to spinning the seed fluff, but I can't say I've had any luck with that. Cattails are native to wetlands across North America.

|

Figure 9.6: Cattail.

|

|

Cedar[905]

[200]

[253]

[325]

[635]

[670]

If it smells like a freshly sharpened pencil, it's probably a Cedar. The inner bark of Cedar can be pulled off in long strips in the late Spring and early Summer. Fresh cut branches one to two inches in diameter give layers of bark 1/16 to 1/8th inch thick. On a good day, the bark will peel around small projecting branch stubs, and down tributary branches. Pounding or retting will yield a fairly strong and soft rope. But if you are in a hurry, the untwisted strips of bark make a reasonable binding for shelters, etc.

|

Figure 9.7: Cedar.

|

|

Corn Husk[265]

[285]

[785]

The dried husks are easily torn into usable strips. Corn Husk isn't particularly strong, but it makes a reasonable string for kitchen use.

|

Figure 9.8: Corn Husk.

|

|

Dandelion

Dandelions came to North America with some of the first European settlers. Originally known for its food and medicinal value, the flower stalks can be used to make cordage. Dandelions now grow in every state and province, from the coasts to the tree line, at least. Many places consider it a noxious weed. Allow the stalks to dry somewhere out of the sun. If they dry too quickly, they crumble like an old rubber band. If possible, don't harvest the stems until after the yellow flowers have passed. They are an important early season nectar source for pollinators. I am not certain how durable dandelion cordage will be. It doesn't show up in many texts, and I first twisted some in the Spring of 2025, in response to a reader's question. Updates as they become available. |

Figure 9.9: Dandelion. |

|

Daylily[742]

[285]

Daylilies were introduced by early Colonists. |

Figure 9.10: Daylily. |

|

Dogbane[325]

[030]

[090]

[480]

[635]

[500]

[670]

[712]

Also known as Indian Hemp since this was the fiber the Native Americans used for most of their ropemaking needs. The fibers are very fine and quite strong. Dogbane does not stretch when wet which makes it useful for holding buckets and pumps together. The fibers can be stripped right from the stalk in late Spring, early Summer. Some people recommend harvesting after the first frost, and working with the dry stalks. I prefer to strip the stalks while they are still green. NOTE: the USDA lists Dogbane as a poisonous plant containing cardiac glycosides. The "bane" in Dogbane means a cause of harm or damage. The Native Americans used Dogbane for centuries without known problems. Use caution, and your judgement. Wash your hands. |

|

|

Elm[285]

[030]

[090]

In the Spring, and early Summer, cut one to two year old branches and shoots, about one quarter inch diameter or smaller. The bark pulls off in long strips. The branches will grow back over time. This is the basis of the traditional woodland management practices of coppicing and pollarding.

|

Figure 9.12: Elm. |

|

Fine Fescue [200]

[770]

Fine Fescues are often part of lawn grass seed mixes, and the plants often escape into the wild, where they grow to usable lengths. The leaves can be over two feet long, yet only 1/32th of an inch wide. Either pulled up by the roots, or cut close to the ground, there isn't much else to do with Fine Fescue other than dry it and twist it. Fine Fescue is very easy to work with. It twists easily. It doesn't have thorns or sharp edges. It also makes a very serviceable rope.

|

Figure 9.13: Fine Fescue. Seed Heads on the Left, Roots on the Right. |

|

Flax[200]

[030]

[290]

[750]

[590]

[755]

Flax makes a good, pliable rope. But Flax is more valuable spun and woven into linen fabric. There are many varieties, some native, others imported by early colonists. All have good, fine, strong fibers. Processing Flax typically involves retting, breaking, scutching, and hatchelling. At two to three tons of fiber per acre, one acre could rig a small trading ship, or string 100 bed frames. The fiber yield for Flax, by weight per acre, can be greater than Hemp.

|

Figure 9.14: Flax. |

|

Giant Foxtail stalks make a reasonably strong cord, if the yarn is one quarter inch or more in diameter.

Suitable for binding crops, for example.

An introduced plant, listed as a noxious weed in several states. |

Figure 9.15: Giant Foxtail. |

|

Grapevine[742]

[090]

[285]

Young vines can be twisted just as they are. Slightly older vines can be used as withies without any further work. From vines more than an inch in diameter, peel the bark off in strips. The inner bark comes off in ribbons about one sixteenth of an inch thick. Grapevine bark makes a stiff rope useful for one-time binding jobs like fences or baskets. Although there are many introduced, invasive, species even native Grapes like Fox and Riverbank Grape are listed in some states as noxious weeds. |

Figure 9.16: Grape. |

|

Hackberry[715]

[254]

The Hackberry tree, also known as the Beaverwood, Nettletree, or Sugarberry, grows on every continent, except Antarctica. It is hardy, grows on poor and polluted soil. It does well in cities, and produces a very nice bast fiber. Oddly, Hackberry does not show up in many texts about ropemaking. Hackberry is in the same family, (Cannabaceae) as Hemp and Hops, although before 2019, it was grouped with the Elms. I have not tried pulling bast fibers from trunk sections, only from small branches. I haven't been around a Hackberry tree that needed to be cut down. In Spring, when the sap is rising, the bark peels nicely off of branches thinner than your finger. Hackberry rope is soft and strong. Nice stuff to work with, nice product when you're done.

|

Figure 9.17: Hackberry.

|

|

Hemp[030]

[140]

[160]

[330]

[405]

[430]

[610]

[748]

[750]

[755]

[770]

[1024]

For centuries, Hemp was the premier ropemaking fiber. So much so that other plants used in ropemaking are often called Hemp, such as Indian Hemp (Apocynum cannabinum), Manila Hemp (Musa textilis), Bowstring Hemp (Sansevieria trifasciata), etc. All Hemp species are imported, but seeds came with some of the first colonists. Traditional processing for commercial Hemp includes retting, drying, breaking, scutching, and hatchelling. However, when the stalks are still green, the outer "bark" layer, the bast fibers, can be stripped off and used with minimal processing after drying. An acre of Hemp can produce 1300 pounds of high quality fiber. That's over eleven miles of 1/4 inch diameter rope.

|

Figure 9.18: Hemp. |

|

Honeysuckle[742]

[285]

[380]

[853]

The one year old vines can be twisted as you would individual fibers. Younger than one year, and the vines are too tender and will break. Two year old vines are too woody, and will snap. The fibrous inner bark, the bast fibers, of the trunk of the woody, bushy Honeysuckles, and leathery inner bark of Japanese Honeysuckle, can also be harvested and twisted. Several of the native Honeysuckles are listed as endangered, but many of the imported varieties, like the Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), and Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) are listed as invasive, banned, and prohibited noxious weeds. Some vines change twist direction while climbing, exhibiting both "S" and "Z" over a stretch of just a few feet. |

|

|

Hops[030]

[340]

[520]

[590]

[770]

Hops is a close cousin of Hemp. Hops fibers were sometimes used as a substitute for Flax.[120] [748] Early in the season, the Hop growers will tear out all but the most vigorous bines (technically Hops grows on Bines, not Vines) so the strongest shoots will climb the strings and mature. At harvest time, the whole plant is pulled up. Either of these times is a good time to get material for ropes. Especially if you offer to help the farmer with the work. The bines are covered with very small curved thorns. Smaller than rose or bramble thorns, they can still scratch you. Hop bines can be processed like Hemp or Flax: retting, drying, breaking, scutching, and hatchelling before spinning. There are both native and imported varieties. |

Figure 9.20: Hops. |

|

Iris

[285]

[380]

[500]

[742]

[905]

Irises are wide spread in the Northern Hemisphere, with several varieties native to North America. The dead leaves at the bottom of the plant can be gathered in late Summer, early Fall. Just twist the leaves as they are, no need for additional retting. Iris makes a nice, soft rope, but not terribly strong.

|

Figure 9.21: Iris Bloom.

|

|

Italian Thistle[785]

The purple flower of the Thistle is the emblem of Scotland. You can make rope from the fibers in the outer layer of the stem. Thistles can grow over six feet tall. Most Thistles were imported, and many are listed as noxious weeds. The fine, sharp spines can be rubbed off with a good pair of leather gloves. The fibers are just under the skin of the stalk. If you make rope from Thistle, be careful you don't spread the seeds.

|

Figure 9.22: Italian Thistle.

|

|

Jute[285]

[600]

[030]

[410]

Jute does not grow in the United States. All Jute is imported.

For demonstration purposes, Jute makes a nice soft rope, although not particularly strong.

|

Figure 9.23: Jute. |

|

Liriope.

Also known regionally as "Lilyturf", "Monkey Grass", or "Spider Grass", Liriope aren't really lilies nor grasses. Liriope has long, thin leaves, similar to a Daylily, but has long spikes of tiny purple flowers. Liriope was intruduced to North America from Asia sometime in the early 1800s. Some varieties are considered invasive. At the end of the season, the older, brown leaves can be pulled and twisted without any additional processing.

|

Figure 9.24: Liriope. |

|

Sedges[742]

[285]

[030]

[080]

[450]

Egyptian papyrus, (Cyperus papyrus), is a member of the Sedge family, and was used to make rope by the Egyptians for centuries. The strongest fibers are in the distinctive three-sided stems. (Sedges have edges...) The Manyflower flatsedge is native in most states south of the Great Lakes and East of the Mississippi. This plant is endangered in Illinois, New Jersey, and Ohio. |

Figure 9.25: Manyflower Flatsedge. |

| Milkweed[090] [253] [030] [500]

[635] [670] [742] [770] [905]

Milkweed is in the Dogbane family, and is used and processed in the same manner. Also like Dogbane, the white latex sap is full of cardiac glycosides. The older the plant, the more poisonous it becomes. Be careful. The fibers are long, and strong, with a silky sheen. Fiber yields can be as high as those for Hemp or Flax. |  Figure 9.26: Milkweed. |

|

Mock Stawberry

Mock Strawberry, is also called Indian Strawberry, Wild Strawberry, and sometimes Snakeberry. This is not the Strawberry you see in the stores; those are from the genus Fragaria. The fruits of the Mock Strawberry are small and round, dry, and have little or no flavor. The five petals of the Mock Stawberry flower are yellow, where the edible Strawberry's flowers are white. For cordage, pull up as many of the runners as you can. Crush the runners while they are still green, then twist them after they've dried. Mock Strawberries are native to Western Asia. They are considered to be invasive in Maryland and Virgina, among other states.

|

Figure 9.27: Mock Strawberry. |

|

Mulberry [253]

[285]

[030]

[742]

Not as strong as Elm bark, but it makes a serviceable cord. Just because silkworms can make some of the world's strongest fibers from this tree, doesn't mean everybody can. You will often see different shaped leaves on the same branch. Some with "mitten thumbs" on the bottom edge, some with two "thumbs", and some without any. The Paper Mulberry was introduced to Virginia in 1603, as part of an effort develop a silk industry.[530] |

Figure 9.28: Mulberry. |

|

Orchard Grass[770]

The stalks and leaves can both be twisted together.

Orchard Grass was introduced by the early colonists. George Washington mentioned it as good feed for cattle.[885] |

Figure 9.29: Orchard Grass. |

|

Oriental Bittersweet[165]

[908]

This is a non-native invasive species, brought to this country in the late 1800s. It is prohibited by law in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. It is listed as a noxious weed in North Carolina and Vermont.[853] The vines can easily grow twenty feet in a year, and will smother and break the trees they climb seeking sun. The bast fibers just under the bark of young vines, smaller than 1/4 inch in diameter, are easily pulled off in long strips. After drying a few days, the outer bark crumbles off without much effort, leaving very fine, strong fibers. Although this is not a Colonial era plant, cutting it down is a public service, and you get good raw materials. Unless you use a strong herbicide, oriental bittersweet will keep coming back, so you will have an unending supply. But if you keep it out of the trees, that's something.

The climbing vines have a characteristic

"Z" twist.

|

Figure 9.30: Oriental Bittersweet. |

|

Palm[200]

[611]

[742]

[285]

[380]

[080]

The fibers on the trunk, under the leaf stalks, and the fibers in the leaves themselves are used in ropemaking. The fibers of the Coconut husk are used in making coir. The Colonial ropemaker could get Palmetto Palm from the Carolinas, but not much further north. Coir would be unknown to an 18th Century Colonial ropemaker.

|

Figure 9.31: Palm. |

|

Pawpaw[065]

[253]

[254]

Also spelled "Paw Paw", or "Paw-paw". This small tree is found from the East Coast to the Mississippi, and from the lower Great Lakes to Northern Florida. The bark of younger twigs pulls off in nice long ribbons. The bark can be split into several layers. The innermost layers make the strongest, most even rope.

|

Figure 9.32: Pawpaw. |

|

Plantain[030]

[285]

Not to be confused with the banana-like plant of the same name. Plantains were introduced by the earliest European settlers and have spread across the continent. The fibers in the leaf stalks are easily pulled from the leaves while green. Together with the roots, these make a tough string. The tall seed stalks can be twisted into a slightly coarser rope. The stalks of the Narrow Leaf Plantain can be over one foot tall. But it takes a lot of plants to make any great length of cordage. Plantain seeds and leaves can be eaten, and the plant has many medicinal properties as well. |

Figure 9.33: Plantains. Broad Leaf (top) Narrow Leaf (bottom) |

|

Red Clover[770]

Red Clover is taller and heavier than White Clover (below). You will need to crush or roll the stalks, then let them ret for a while. After that, the dried stalks can be rubbed between your palms to get workable fiber. Red Clover was introduced to the Americas by European settlers as early as the 1600s.

|

Figure 9.34: Red Clover. |

|

Rosemallow[030]

[905]

Rosemallow, or sometimes Mallow Rose, Hearty Hibiscus, or Swamp Mallow. The Rosemallow is native to the South Eastern United States, but can grow as far north as Canada, and west into Texas. Bark fibers, pulled from the stems of this tall plant make a strong cord. You can get usable fibers in the spring, but if you wait until after the plant has gone to seed, you get flowers, fibers, and seeds for next year's crop. Retting is required if you want a finer fiber. Rosemallow is in the same family, (Malvaceae), as the commercially important Jute plant, see above.

|

Figure 9.35: Rosemallow. |

|

Rushes[742]

[020]

[030]

[090]

[500]

[380]

[265]

Rushes are native in most of the Northern Hemisphere. Used in basketry, thatching,

and ropemaking, the stalks are dried, and used whole.

|

Figure 9.36: Rushes. |

|

Spanish Moss[742]

[090]

[840]

Used by the Native Americans around the Gulf of Mexico for making rope and blankets. Spanish Moss grows as far north as the southern edge of the Chesapeake Bay. Spanish Moss isn't really a moss, but a relative of the pineapple family. It is an epiphyte, not a parasite, which means it doesn't draw nutrients from the host tree. Big accumulations can be a problem in heavy rain and high winds because of the additional stresses put on the branches of the host tree. Without retting, the rope you can make will be fat and fluffy. Not a strong rope for critical situations. Retting removes the spongy grey-green outer layer, and leaves an almost black core like coarse beard hair, or soft steel wool. But retting has the associated nasty smell. The moss can also be dried and rubbed to clean. But drying Spanish Moss presents a few problems. The plant is an epiphyte, it lives off the moisture it gets from the air. Pluck a bunch from a tree, put it in your back yard, and it will continue to survive.

If you bury Spanish Moss in the sand, it will eventually die from lack of sunshine, and the sand will help scrub off

the outer layer.

|

Figure 9.37: Spanish Moss. |

|

Stiltgrass[853]

An invasive species introduced to the United States around 1919. Makes a coarse rope suitable for binding crops or thatching. Japanese Stiltgrass is banned, by law, in Connecticut, prohibited in Massachusetts, and listed as a noxious weed in Alabama. Dew retting for a week or so makes the stalks more pliable. The seeds are small and hard to see. Moving a Stiltgrass rope from one place to another can spread this invasive pest.

|

Figure 9.38: Stiltgrass. |

|

Timothy[285]

[770]

Timothy Grass was introduced to the Colonies in the early 1700s, and known to George Washington[770] and Benjamin Franklin. Timothy can grow to be almost five feet tall, and has a long, tight, sausage shaped seed head, around 3/8 inches in diameter. Both the stalks and the leaves have good fibers for twisting. |

Figure 9.39: Timothy Grass. |

|

Tulip Poplar[285]

[380]

The Tulip Poplar isn't really a member of the Poplars (Populus spp.), but is more closely related to the Magnolias (Magnolia spp.).

The inner bark from freshly cut trees and larger branches can be used

immediately, or dried for later use. Some sources recommend boiling with wood ash for up to an

hour[670],

but I haven't seen any improvement.

|

Figure 9.40: Tulip Poplar. |

|

Vetch

The name Vicia comes from the Latin "vincire" meaning "to bind or tie up." The dried stems make good cordage. You might need to pound or roll the tougher, older vines to loosen the fibers. The tendrils at the ends of the vines often reverse their direction of twist when attaching to a climbing support.

|

Figure 9.41: Vetch. |

|

White Clover[770]

The flower stalks and the ground runners make a reasonable cord. |

Figure 9.42: White Clover. |

|

Wisteria

[285]

There are native American species of Wisteria, as well as several imported species. Some of the imported varieties are invasive, but they are all quick climbers. Wisteria vines are known for their large, showy, hanging flowers. But what you want are the long runners growing along the ground. These will be about as thick as a pencil, and run for many feet. Any time from Spring through Fall, pull up several feet of runners, and peel off the bark. It should come off in strips a foot long or more. Let it dry, and the outer bark will crumble off with just a little bit of work. The bast fibers can be divided quite fine, and three-ply cordage 1/16th inch in diameter is very doable, if you should have the need. Makes a strong, smooth rope. Bark stripped off the climbing vines is a little coarser than that from the runners, and there are more side branches to work around.

|

Figure 9.43: Wisteria: Leaves (top) Peeled Vine Bark and Sapwood (bottom).

|

|

Yucca[030]

[285]

[325]

[400]

[498]

[500]

[635]

[742]

Sometimes called "Adam's Needle". [715] The old, dry leaves at the bottom of the plant are usually pre-retted. All you need to do is rub them between your palms to work out the fibers. Yuccas are native from Florida to Massachusetts, and Virginia to California. Commercially grown sisal (Agave sisalana), often seen in hardware stores as binder twine, is a close relative of the yuccas. You can grab the sharp point on a green leaf, and pull off several fibers over a foot long. This makes a handy needle and thread arrangement for quick sewing repairs.

|

Figure 9.44: Yucca.

|

Beach Wrack is the vegetable matter that washes up on the beach after a storm. It's made up of parts of seaweeds as well as land plants that have washed into the ocean. By the time it reaches the beach, it's been well retted, and tumbled about. The exact plants will depend on the season, and where you are looking. It might also contain bits of old fishing nets, ropes, and fishing lines.

A good fresh water soaking is needed to get rid of the salt, sand, and any clinging sea life. The wrack I've used makes a stiff, coarse rope.

The man-made stuff, especially the ropes, can be repurposed as mats or boat bumpers, things like that. Or take it to the landfill. Don't leave it on the beach. It tangles up the sea critters and makes ropemakers look bad.[622]

In Japan, paper has been made into "mizuhiki" string for centuries.[783] [807]

Rag ropes are good for protecting things from bumps and scratches. They can also be useful getting out of a window.

| Chapter 8 | Introduction | Chapter 10 |

| Colophon | Contacts |